(June 28, 2023) – Forrest Lucas learned his work ethic in a cattle barn. When you look at the Lucas Oil Stadium, home of the Indianapolis Colts; see Lucas Oil promotions at many NASCAR and Indy racetracks in America; watch a Professional Bull Riders event and see Lucas Oil signage on the chute gates; or buy various Lucas Oil products you might think it’s owned by just another rich tycoon. You would be wrong.

“Forrest and Charlotte Lucas are truly humble, genuine people,” says one of their associates with Lucas Cattle Company. Indeed, they are friendly and approachable at a level that surprises those who don’t know them… yet.

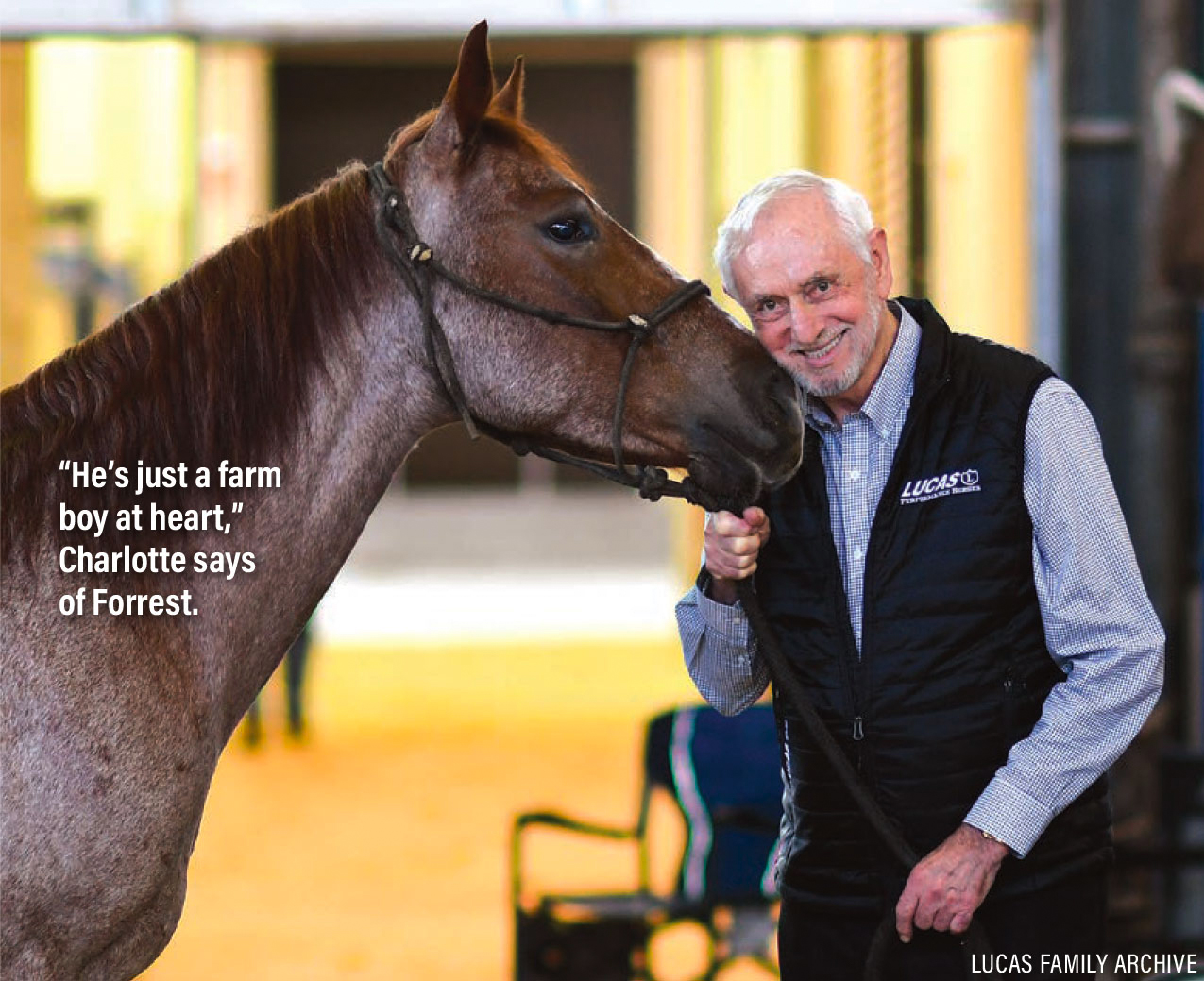

“He’s just a farm boy at heart,” Charlotte says of Forrest. Long before he found himself up to his elbows in oil and grease, he worked showing and fitting cattle. “He missed a few weeks of school every year because he was showing cattle at the Kentucky State Fair or the Indiana State Fair,” she says.

Forrest says he started showing and fitting cattle when he was 12 years old. That job fell through when he was 15 and he went to work for another cattleman. “His wife, she was a real good cook,” Forrest remembers. When you’re a hard-working teenager, that counts for a lot.

So, they asked Forrest to live with them and manage the show cattle. “I stayed there for two years, until I got out of school, and showed cattle all summer long.” He traveled as far as West Virginia, taking a semi-load of cattle to shows. “That was the first time I drove a truck,” he says.

But life takes people in directions they never planned, and so it was with Forrest and Charlotte. The two are truly a team; they have worked side by side the entire time they have been together.

In their early years, they owned a small trucking company, which became the genesis of Lucas Oil. As their success with Lucas Oil shot upward, Forrest began recalling his teenage years working with cattle.

“He said, even then, they were breeding cattle for the wrong purposes,” Charlotte says. “They were breeding them for the show ring and not for the type of meat that you could ultimately get in the grocery,” Charlotte remembers.

RETIRING WITH A FEW ACRES AND A FEW HEAD

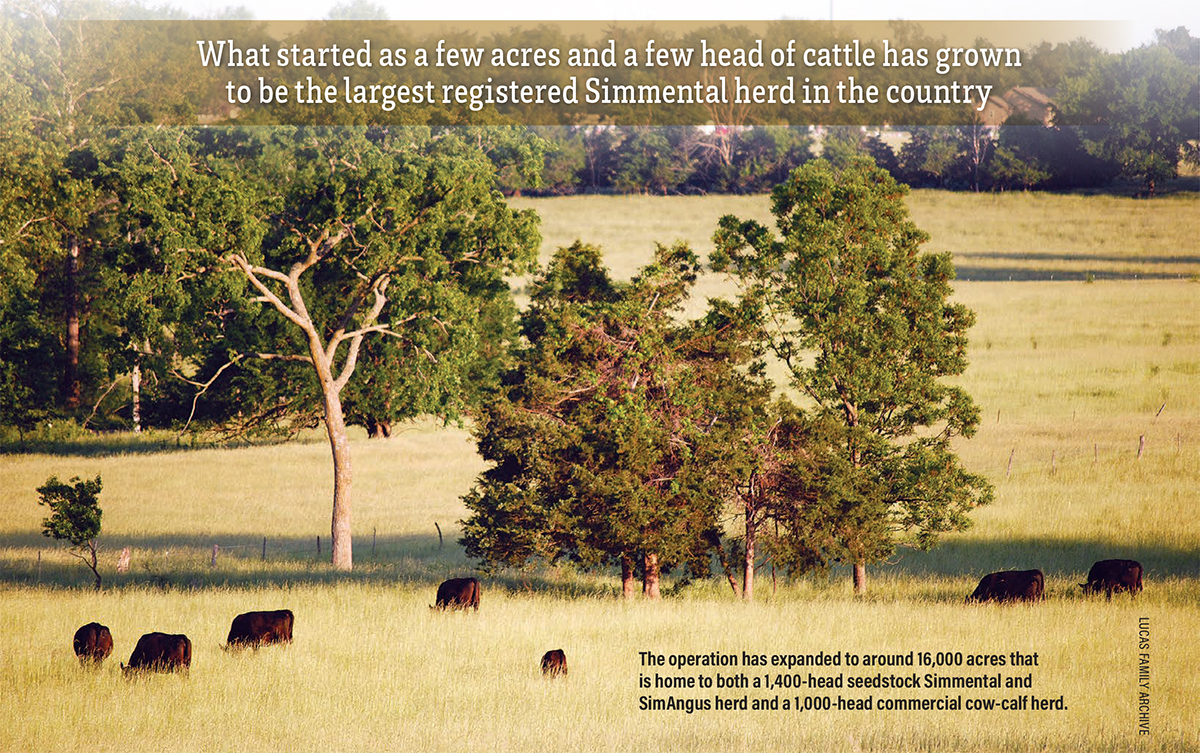

“So, when he decided to do this (get into ranching), he told me, ‘When I get ready to retire, I want to get a few acres and have a few head of cattle.'”

Remember, this is Forrest and Charlotte Lucas at the steering wheel. They bought their initial piece of ground in 2000 — 3,450 acres in western Missouri, roughly halfway between Springfield and Sedalia. Since then, the operation has expanded to around 16,000 acres that is home to both a 1,400-head seedstock Simmental and SimAngus herd and a 1,000-head commercial cow-calf herd.

Lucas Cattle Company is now the largest registered Simmental seedstock operation in the country. Depending on what their bull buyers are looking for, they offer everything from half-blood SimAngus up to purebred Simmental. Using genomically- enhanced EPDs, they focus on keeping birth weights in check, while maintaining solid growth, marbling, and maternal traits.

Achieving a positive genetic mix of those traits is tough. For example, keeping birth weights acceptable yet achieving strong weaning and yearling weights are antagonistic traits. “It’s the curve-bending type of genetics we’re trying to accomplish,” according to Forrest. “We’re trying to be a leader.” His goal is to achieve the genetics that breeders with smaller herds want to achieve, yet don’t have all the resources to do so.

Lucas Cattle Company gets that done by being large enough to do everything in-house. “A lot of top breeders work with multiplier herds,” Forrest says. “We don’t have to do that. It’s all right here on the same farm.”

In addition to stressing genomically- enhanced EPDs, the operation recently moved heavily into embryo transfer. That began with the purchase of WS Miss Sugar C4, one of the all-time high-ranking females in Simmental history.

Geneticists talk about economically important traits versus convenience traits. In Forrest’s mind, one is just as important as the other. “One thing about our cattle,” Forrest says. “They’ve got real good attitudes.” Beyond disposition, they look for good feet and legs and good udders. “Those are the things we have concentrated on since we first started,” Forrest says.

From a management perspective, Lucas Cattle Company has its registered and commercial herds split into both spring and fall calving seasons. “We try to get our calving season down to 45-60 days if we can,” Forrest says. “We do our embryo work along with our AI program first, then the bulls get kicked out around Thanksgiving for the fall calvers, and around the first of May for the spring calvers.

Replacement heifers are selected based on both visual appraisal and EPDs. They’ll keep around 200 registered heifers and around 150 commercial heifers. “We use highly selected herd sires because we know, with AI, it would take an army to try to AI that many cows. So we do the embryo work, AI, then run the herd bulls after that,” Forrest says.

MARKETING CALVES

The commercial herd is managed much the same as the registered herd in terms of calving season and other aspects. When it comes to marketing, however, they’re in a unique partnership with Purina. “Purina has a research station, and we send a lot of calves up there for Purina to do testing,” Forrest says. That provides them with carcass data, “which is good when you’re talking about sire evaluation.”

A good portion of the commercial calves go to a sale barn in nearby Windsor, Missouri, and then they’ll retain ownership on some and feed them out. While that provides important data, their long-standing relationship with Purina has been the proving ground on sire groups, genetic advancement, and other aspects of honing their program to a fine edge.

PASTURE MANAGEMENT

“This is Missouri, so it’s fescue,” Forrest says. That’s a bittersweet thing because endophyte-infected fescue can cause lots of problems with fescue toxicity if it gets too mature. “But the good thing about fescue, it will grow in cold weather a lot better than anything else in the world,” Forrest says. “When you need it, it’s there. It’s hardy, it’s tough.”

But Forrest has always been curious, always looking for ways to do things better. So, he contacted several agronomists at the University of Missouri-Columbia to work with them to improve their grazing management by improving the forage. Long-term, the results of that collaboration could help other beef producers improve their fescue as well. Beyond just the research results, Lucas Cattle Company will eventually host field days and tours to show others how the research works under production conditions.

The ranch isn’t all fescue pastures, however. There are plenty of acres with other cool-season grasses along with legumes in the mix, which produces hay and haylage, as well as late-season grazing. “A lot of ground that’s just really good for cattle to roam around on,” as Forrest puts it. “A lot of hills and a lot of creeks.”

However, of all the quality cattle that call Lucas Cattle Company home, it’s their small Longhorn herd that impresses many the most. According to Forrest, unless visitors come to the ranch specifically to look at the registered cattle, it’s the Longhorns that take the spotlight. “Beautiful, beautiful, beautiful, our Longhorns,” he says. “They (non-cattle visitors) don’t pay attention to the black cows. Everybody will stop and take pictures of those Longhorns.”

Among the many things that are part of the Lucas business holdings is a golf course. Yet neither Forrest nor Charlotte plays golf. The ranch, Charlotte says, is their version of golf. It’s where they go to relax and recharge.

And it’s not just some of the best cattle in the country grazing lush, green pastures. It’s the entire ranch with its abundant wildlife. Beyond the white-tailed deer and wild turkeys, Charlotte particularly enjoys watching the eagles. “We have a little bit of every kind of animal on the ranch,” she says, “and it’s fun to just drive around and see.”

Meet WS Miss Sugar C4

The genetic foundation for Lucas Cattle Company going forward is one of the most prominent and genetically superior cows in the Simmental breed. Forrest and Charlotte bought Miss Sugar in 2023 for what is likely a record price for a female.

With Miss Sugar at the genetic forefront of their extensive embryo transfer program, Lucas Cattle Company aims to produce curve-bending bulls. “We’re using her and some of her daughters along with other donor cows to try to accomplish the genetic spread with low birth weight, high growth, high marbling, high cow retention, high API (All-Purpose Index), and high TI (Terminal Index),” Forrest says.

For the Simmental breed, the API index identifies cattle with the genetics to produce strong maternal and stayability traits. The TI index identifies cattle with the ability to produce calves well-suited to the carcass and feedyard performance.

“She has the curve-bending type of genetics we’re looking for,” Forrest says. “She’s in the top 10% for 13 genomically important traits along with being in the top 1% for marbling, API, and TI. She is a standout in the breed and can do everything we’re working towards. And that’s what we’re trying to do with the entire herd.”

And the best is getting better. When you look at a seven-year-old cow (as this was written) her genomics usually don’t change very much, Forrest observes. The accuracies are pretty well set. “But she recently went up $5 on the API index and that’s not very common. She’s right up there at 190,” he says.

“That makes Sugar a unique outlier for our herd,” he says. “Sugar’s elite genomic profile along with her flawless phenotypic style makes her a valuable cornerstone for our breeding program going forward. So, we’re trying to propagate those kinds of genetics.”

Protect The Harvest

One of the ways that Charlotte and Forrest Lucas are giving back is through Protect The Harvest, an organization founded because of a Humane Society of the United States (HSUS) incursion into Missouri politics.

Forrest got a call from one of his cowboys asking if it was OK to hang some signs on the fence. As the cowboy explained what HSUS was up to, Forrest became alarmed. Then he went into action. On the surface, the 2010 legislation was about puppy mills. “What they wanted to do is to stop people from having any kind of ownership of an animal,” Charlotte says. While Forrest jumped in only two weeks before the election and was significantly outspent by HSUS, the effort to put a plug in the legislation worked.

HSUS came back in 2011 with the same effort, but this time Forrest and others were ready. They killed that effort as well. Once Forrest knew what animal owners were up against, he decided to fight back on a national scale. “About two days after the election, he comes back to the house,” Charlotte remembers. “And he says, “By the way, honey, I started a 501 (C) 3.'”

And in 2011, Protect The Harvest was born. According to Mike Martin, the group’s chief communications officer, the mission is based on a three-pronged approach — informing people about the true agenda of animal rights and antiagriculture extremists; protecting the freedoms and way of life that supports agriculture, land use, hunting and fishing, animal ownership and animal welfare; and responding to laws, regulations, and misinformation that would negatively impact animal welfare and animal ownership, restrict rights and limit freedoms.

“What we are doing and continue to do is better inform people who don’t know about (animal rights extremists), so they can make informed decisions at the ballot box,” Martin says. “It’s all about what we call ‘A Free and Fed America.'”

From the Working Ranck Magazine Summer 2023 edition. Written by Burt Rutherford.